Giving a voice to the voiceless – Malian activist Fadimata Walett Oumar strongly believes that women hold the keys to a more peaceful future in the Sahel

Malian activist and Tuareg musician Fadimata Walett Oumar is a long time battler for peace and women’s rights. She strongly believes that with the right investment in their education women hold the keys to a more peaceful future across the conflict-ridden Sahel.

“Every mother needs to talk to their kids and say that terrorism is not a solution,” says Malian activist Fadimata Walett Oumar. Photo: Maria Santto/CMI.

Growing jihadist violence in the Sahel region threatens the stability of the African continent. While the violence continues to expand into new areas, it has become increasingly clear that fighting terrorism militarily will not bring about peace.

Public frustration with Sahelian governments is growing, exemplified by unrest leading to recent military coups in the region. In Mali, one of the epicentres of the recent violence, people live in constant fear, says activist and musician Fadimata Walett Oumar.

“I don’t understand how the armed groups are able to advance with this military presence. Every time someone says these groups have been defeated, they come back with force. Many people in the Sahel are as puzzled as I am.”

Walett Oumar is a long time battler for peace and women’s rights, and also a famous Tuareg nomad singer “Disco”, who plays desert blues with her band Tartit. She was one of the speakers at the Fifth National Dialogues Conference that brought about 120 peace mediation experts from 30 different countries to Helsinki on 15-16 June.

The disillusionment of young men lies at the heart of the problem in the Sahel. With no jobs and education, they are easily recruited by terrorist groups who can offer them a lot of money.

“Preventing terrorism in the region is about giving these young men a better future. One really has to put in place big development projects for the Sahel. Who would want to die fighting if you have better options? After all, these young men don’t know if they are going to come back alive or not when they join these groups,” says Walett Oumar.

Fadimata Walett Oumar with other women at Sag-Nioniogo refugee camp in Burkina Faso in 2014. Photo: Marta Amico.

“Every mother needs to talk to their kids”

Nomadic Tuareg communities in Northern Mali bear the high cost of terrorism. To ease the problem, Walett Oumar emphasises the role of women. Her work coordinating the association of Tuareg women in Mali deals greatly with raising awareness about how women can prevent violence.

“Every mother needs to talk to their kids and say that terrorism is not a solution. Many don’t even know if their sons belong to these groups or not.”

She gives an example of the need for advocacy, describing how many Tuareg women are not aware of how illegal gold mining feeds terrorism in the North of Mali.

“Obviously the mining gives jobs to their sons, but the profits go to the pockets of the terrorists, fuelling violence.”

Tuareg womens’ ability to make a difference is hampered by their marginalisation. Many are uneducated and illiterate. This, coupled with security problems and physical distance, makes it hard for Tuareg women to participate in different peacemaking efforts in Mali.

Walett Oumar thinks that women hold the keys to a more peaceful future across the Sahel if there is investment in their education. In Mali, for instance, the mere presence of women has put issues such as education and health on the agenda, as opposed to security matters that men often focus on. Women’s inclusion has fostered direct and definite change in different communities.

“Bringing change is about supporting ordinary women. My mission is to speak for those who don’t have a voice so that they can have one.”

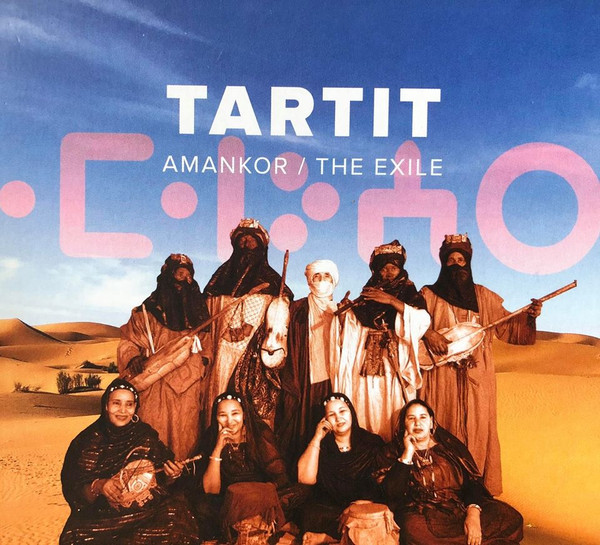

The cover of Tartit’s “Amankor/The Exile” album, released in 2019.

Songs of unity

Walett Oumar’s activism is strongly shaped by her personal experiences, in particular by years of exile.

“The fact that I have been a refugee several times has shown me the very negative side of war. My experiences have increased my strength to fight for peace. When we have peace, I know we can find ways to help people. But when we have war it is not possible. Then people help terrorists because they give you some money. It’s a desperate situation that make people do the things they do.”

In the early 1990s, the Tuaregs took up arms against the governments of Mali and Niger. Like the majority of her fellow citizens, Walett Oumar also had to flee the violence. She lived in refugee camps in Burkina Faso throughout the 1990s.

It was there, in 1995, that the desperate situation of refugees led her to form both the association and the band.

In the early 2010s, she returned to the same camps three times as the current crisis unfolded with the Tuareg rebels joining forces with Islamist militants.

The insurgency was quickly hijacked by jihadists who tried to impose a strict Sharia law in the north. This meant that one of the richest reservoirs of music in the African continent dried out for a time. Musicians had their instruments smashed. Radio stations were torched. Playing music was punished by whippings, even prison time.

The situation was particularly difficult for Walett Oumar and her group, one of the first Tuareg bands initially composed entirely of women. Tartit had played her part in bringing Tuareg music to the world stage, but with the jihadist takeover the band ended up being split between refugee camps in Mauritania and Burkina Faso.

Music plays an important role in the lives of Tuareg women, giving them liberty and a voice.

“Life without music is not possible, and for me personally I would rather die than never be able to perform, create or listen to music again in my life,” Walett Oumar explained in 2013.

Now the band has produced its fourth album, and is ready to tour again after coronavirus pandemic.

In the Tamasheq language of the Tuareg, “tartit” means union or unity. The songs are not just about the unity of Tuareg people but also the need for unity among all Malians, regardless of sex or ethnic group.

“Our music is very much about peace.”

Antti Ämmälä/CMI